Two-Dimensional Kinematics

The basic idea to extending the study of kinematics to two dimensions is surprisingly easy: horizontal and vertical motions are independent. Or, in other words, each motion behaves as if the other motion were not present. The TL:DR version of this tutorial is: Everything works just as it used to in one dimension, including the symplectic integration.

In what follows, we will give a geometrical explanation as to how two-dimensional motion works, the internal computations, using symplectic integration, do not change, however.

To code information about movement in more than one direction, vectors are used. In this tutorial, all vectors are

elements of the standard two-dimensional vectors space

Let

Please note that, unlike in one dimension, the graphs of the position and velocity functions are no longer subsets of

Position and Displacement

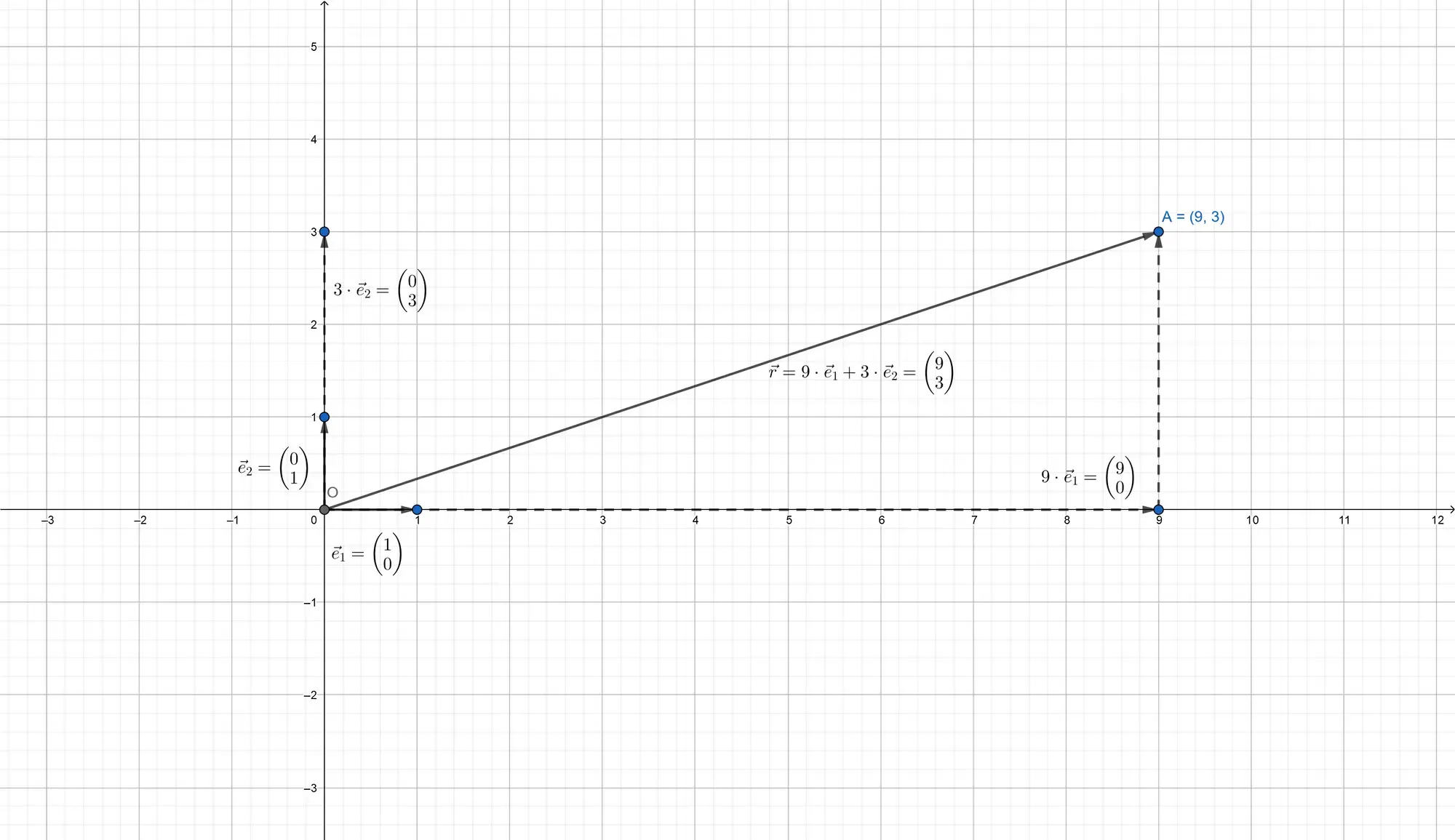

The position of an object is coded in a two-dimensional vector

Please note that in the standard plane, vectors correspond to the points they are pointing to. The position of the object is equal to the position of the point A in the figure above.

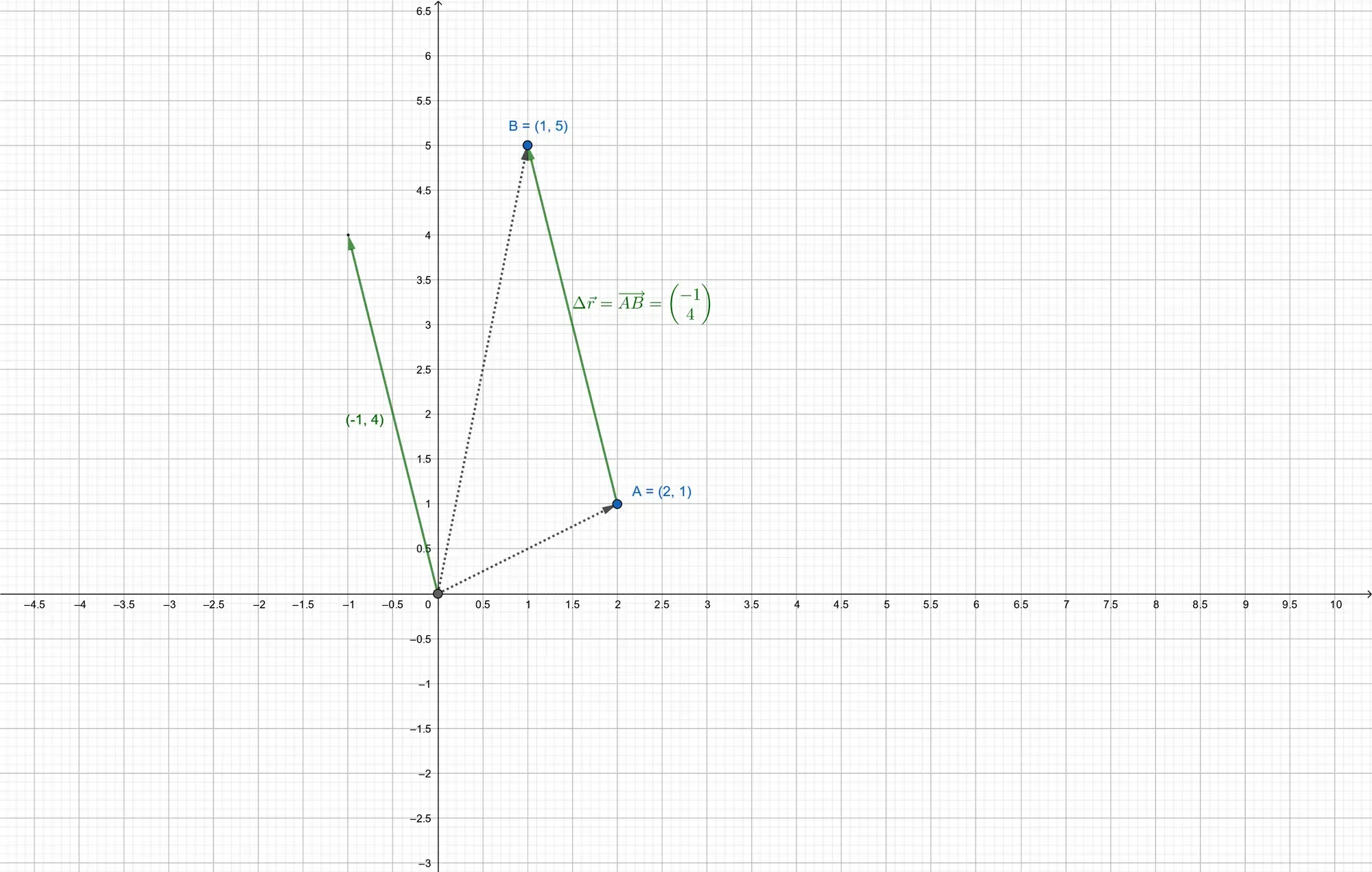

The two-dimensional displacement of an object can then easily be computed as

The displacement vector can be considered the vector joining two points in the plane and its coordinates are the

difference of the coordinates of the end point

Velocity and Speed

As in the one-dimensional case, the average velocity vector

As an example, assume that a dog is observed initially at the position

Note that as stated in the introduction, both average velocities are completely independent of each other, or, in other words, we would have got the same result, had we computed them separately one after the other. Try it out if you don’t believe me.

The instantaneous velocity

To actually compute the speed

Please note that, as before, the vector of the instantaneous velocity shows the direction an object is moving in. The *

direction*

As an example, imagine a trout swimming around with a velocity of

It might also be interesting to note that when one is only interested in comparing the speed of two objects, it is not

necessary to compute the square root. Let

While computing the square root is no longer as costly as a few years ago, saving some computational time (for free) is always a good thing!

Acceleration

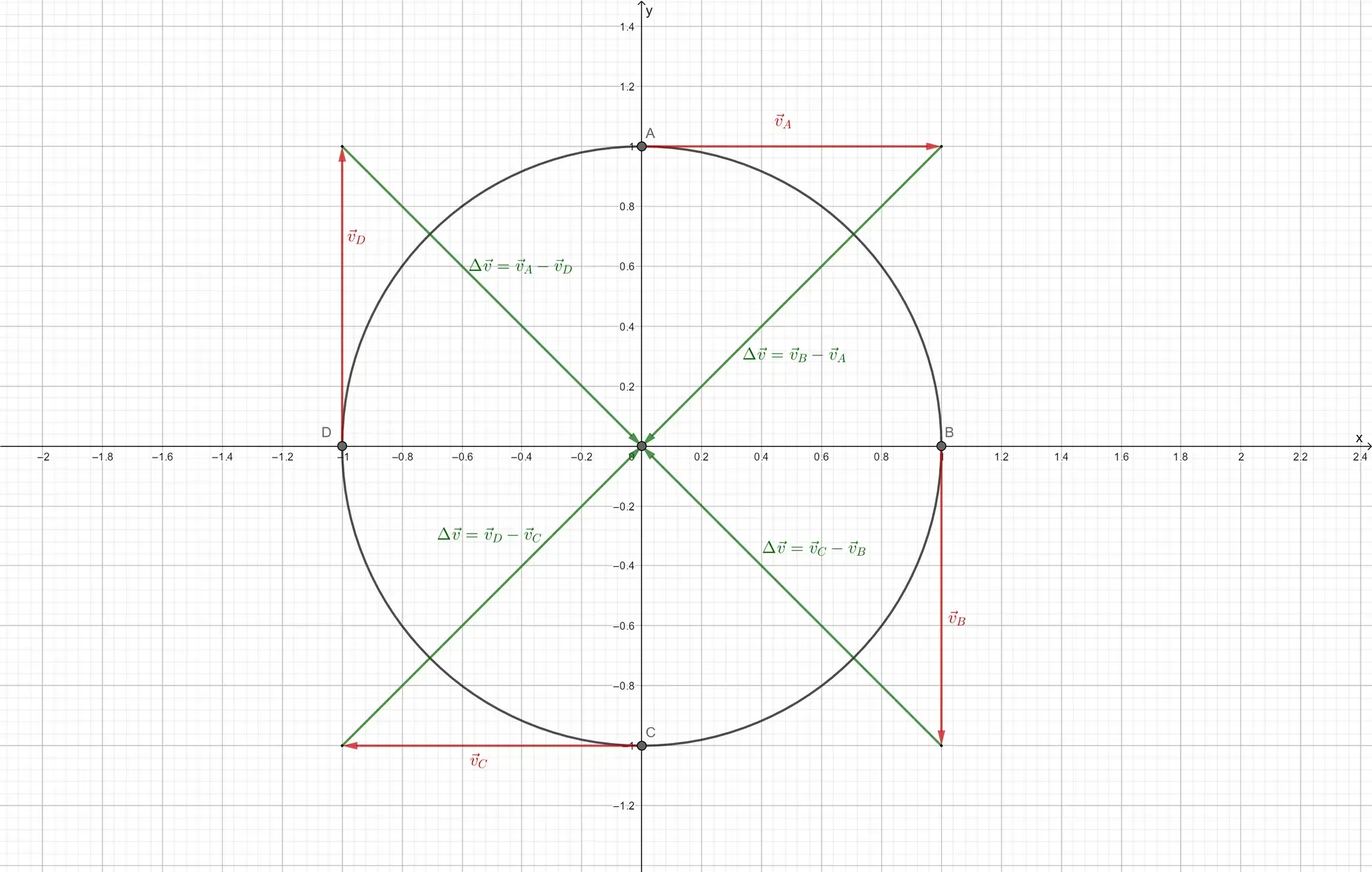

The average acceleration vector

In the figure above, the car drives at a constant speed, but the velocity changes as it’s the direction of motion keeps changing. Which means that the car accelerates without changing its speed.

Also note that the direction of the acceleration need not point in the direction of motion, it won’t do so in most cases.

The instantaneous accelerations

I created a primitive Geogebra applet to let you toy around with a particle, called Cosmo, moving around a winding path. Use the slider to move Cosmo around, and see how the velocity and acceleration vectors, computed using the derivative, change. You can use the mousewheel to zoom in and out, and holding the left mouse button allows you to move the viewport. Alternatively, click here, to open the applet in GeoGebra.

Implementation

As stated in the introduction, nothing really changes when it comes to approximating a discrete solution to the

equations of motion. Recall that

The C++-code for the symplectic integrator thus remains impertinently easy:

void Kinematics::semiImplicitEuler(mathematics::Vector2F& pos, mathematics::Vector2F& vel, const mathematics::Vector2F acc, const double dt){ vel += acc * dt; pos += vel * dt;}As a little demo, I started an alien invasion:

util::Expected<void> PlayState::update(const double deltaTime){ if (isPaused) return { };

// get meters per pixel const float mpp = physics::Kinematics::metersPerPixel;

// update position based on symplectic integration of the equations of motion for (unsigned int i = 0; i < centers.size(); i++) { // symplectic integrator: semi-implicit Euler physics::Kinematics::semiImplicitEuler(centerVecs[i], velocities[i], accelerations[i], deltaTime);

// wrap screen unsigned int width = dxApp.getGraphicsComponent().getCurrentWidth(); unsigned int height = dxApp.getGraphicsComponent().getCurrentHeight();

if (centerVecs[i].x > width) { centerVecs[i].x = width; accelerations[i].x = -accelerations[i].x; velocities[i].x = -velocities[i].x; }

if (centerVecs[i].x < 0) { centerVecs[i].x = 0.0f; accelerations[i].x = -accelerations[i].x; velocities[i].x = -velocities[i].x; }

if (centerVecs[i].y < 0) { centerVecs[i].y = 0.0f; accelerations[i].y = -accelerations[i].y; velocities[i].y = -velocities[i].y; }

if (centerVecs[i].y > height) { centerVecs[i].y = height; accelerations[i].y = -accelerations[i].y; velocities[i].y = -velocities[i].y; } }

// return success return { };}

You can download the source code from here.

So far the symplecticness of the semi-implicit Euler method has really worked out quite well for us. Handling motion, in any dimensions, is totally easy!

In the next tutorial, we will learn how to simulate projectile motion! Fire in the hole!

References

- Geogebra

- Physics, by James S. Walker

- Tricks of the Windows Programming Gurus, by A. LaMothe

- Wikipedia