The Game Loop

The game loop is the heart of every game. It is well known that a healthy heart is the key to longevity. As briefly mentioned in the last tutorial, it is preferable to have the heart beat with a fixed frequency, else numerical instability might occur while doing mathematical computations, endangering not only the heart, but the health of the entire body.

We will now discuss four ways to implement a game loop.

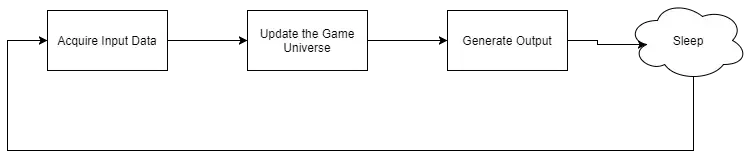

Unlimited FPS

The game loop implemented in the last tutorial seemed almost natural: updating the game objects based on the time

Meet the bad guy, my ancient nemesis: numerical analysis! And numerical analysis is so evil, it will turn this beautiful game loop into a non-deterministic hell!

Actually, this game loop has problems both on slow and on fast machines. Think back to the poor student running around campus, trying to avoid the professors.

As the game slows down, the game world will be updated in bigger steps, resulting in rougher animations, and a lower reaction time both for the player and the AI-controlled professors. The difference between

Okay, so this is bad on slow computers, but what about fast computers? Surely, animations are smooth now and the reaction time is ideal. Well, the simple fact that the memory space of computers is limited, leads to the explosion of rounding errors. Let us use PARI/GP, a computer algebra system designed for fast computations in number theory, to show what catastrophic damage rounding errors can lead to, even when using floating-point arithmetic with very high precision. The effects seen here will be even worse in C++.

Now assume that the poor student is walking around the campus at the average speed of an average human being:

At first, the student is in a part of the campus that the game can run in

? speed=(3*1000)/(60^2)*1.0= 0.83333333333333333333333333333333333333? distance1=0= 0? ticks1=0= 0? spf1=1/60*1.0= 0.016666666666666666666666666666666666667? while(ticks1<10, distance1+=speed*spf1; ticks1+=spf1)? distance1= 8.3472222222222222222222222222222222170Now clearly

so, what happened? We broke one of the most important rules of numerical analysis: While doing so many additions, the roundoff errors from the non-exact representations of speed and spf exploded on us.

But still, let us continue with the game. After moving around, the student is now at a more quiet place of the campus that the game can handle with

? speed=(3*1000)/(60^2)*1.0= 0.83333333333333333333333333333333333333? distance2=0= 0? ticks2=0= 0? spf2=1/120*1.0= 0.0083333333333333333333333333333333333334? while(ticks2<10, distance2+=speed*spf2; ticks2+=spf2)? distance2= 8.3402777777777777777777777777777777720Okay, now, not only is

but also

and

? distance1= 8.3472222222222222222222222222222222170? distance 2= 8.3402777777777777777777777777777777720? distance1-distance2= 0.0069444444444444444444444444444444450035So the difference between

Numerical analysis has truly turned this promising game loop into a nightmare: the game is no longer deterministic and just imagine what those roundoff errors could do to the physics engine, or simply ask the U.S. Military about the Patriot System.

Conclusion: The effects of numerical instability can be as subtle as the game feeling slightly different depending on the frame rate or as extreme as objects moving through walls and jumping to outer space. It is utterly unrealistic to expect mathematical stability with a fluid framerate. Thus, even though this game loop is featured in many prominent books about game programming and various famous online tutorials, there can be only one final verdict: Guilty. Game over!

Constant FPS

A first solution would be simply to take a nap if things are going too quickly. To run the game with constant

Here is an example for a game loop with constant

// set constant frame rate of 60 frames per secondconst int constantFPS = 60;const double constantMSPF = 1000 / (double)constantFPS;

for(;;) timer->tick(); if (!isPaused) { // sleep if things are going too quickly Sleep(constantMSPF - timer->getDeltaTime());

// acquire input

// now update the game logic based on the input and the elapsed time since the last frame update();

// generate output }}What happens if it takes longer than

If the hardware is powerful enough and if the algorithms are carefully designed, everything goes well: For example, if it takes

Conclusion: This is a not-so-good idea for a game loop. It is easily implemented, and writing a physics engine based on a fixed framerate is easy. On mobile devices, it could save battery power. It is problematic on slow machines, though, and it hinders scientific progress.

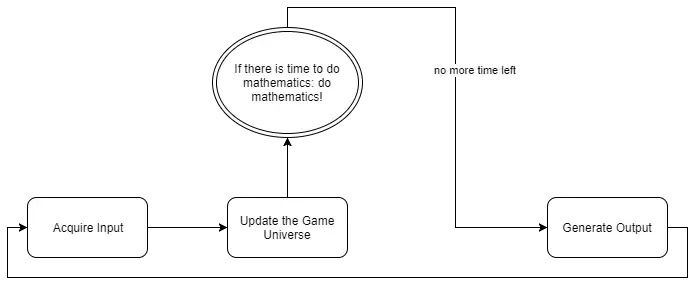

Mathematical Freedom

Thinking about the problems of both game loops above, it becomes clear that we want the best of both worlds. We want

const int constantFPS = 120;const double dt = 1000/constantFPS;double accumulatedTime = 0.0;

for(;;){ timer->tick(); if (!isPaused) { // acquire input

// get time elapsed since the last frame accumulatedTime += timer->getDeltaTime();

// now update the game logic based on the input and the elapsed time since the last frame while (accumulatedTime >= dt) { update(dt); accumulatedTime -= dt; }

// generate output }}At the beginning of each frame, the accumulated time

In the above example,

On slow computers, this might lead to very long update loops. For large

On faster computers, this game loop no longer suffers from the numerical instability of the Unlimited FPS game loop, but it still wastes CPU cycles, just as the Constant FPS game loop did.

Conclusion: While this game loop is a significant improvement over the two others, there is still the problem of having to manually define a value for

Far Seers

Accumulating the leftover time in the previous game loop is not only wasting precious CPU cycles, no, the fading away of time created a nightmarish ghost, hiding in the shadows of an uncertain future, ready to jump on an unprepared programmer at any moment; and when it does, the game world will be rendered at a point between two updates.

Continuing the above example, imagine the game running at

It seems obvious that in most cases

For example, think about the student moving across the campus. He just found a t-shirt of his favourite hero, Flash, granting him the power of lightning fast speed. What happens when the student zooms horizontally over the campus, from the left edge of the campus to the right edge, at the moment the game renders between two updates. The student should be seen moving towards the middle of the campus. Yet at the first update, the student is at the left edge, then the game world is rendered, with the student still seen at the left edge of the campus, leading to very rugged movements.

Thankfully, all the information needed to solve this problem is already available. After updating the game, the time left over is stored in

Assume that the renderer knows the position and the velocity of each object in the game. Further assume that the student, with his Flash t-shirt, is moving to the right by

Obviously, far seeing is always perilous, for example, when the next game update is done, it is discovered that the student actually hit a tree, standing firm at position

The analysis of this new game loop in the case of a slow computer is the same as for the previous game loop.

On fast computers, things will run as fast as they possibly can, and with the rendering function peeking into the future, no more stuttering will occur.

Conclusion: While this game loop design might make coding the rendering function a bit more difficult, it is clearly the superior of the four designs shown in this tutorial, thus, from now on, this will be the game loop design used.

Putting It All Together

Here is the new game loop implemented in C++, with

I changed a few of the members of the DirectXApp class to be private, basically making them constants. Clearly, no other parts of the game need to alter those. Most of the variables needed and used by the derived DirectXGame class are still protected:

class DirectXApp{private: // folder paths std::wstring pathToMyDocuments; // path to the My Documents folder std::wstring pathToLogFiles; // path to the folder containing log files std::wstring pathToConfigurationFiles; // path to the folder containing the configuration files

bool validConfigurationFile; // true iff there was a valid configuration file at startup bool activeFileLogger; // true iff the logging service was successfully registered

// timer Timer* timer; // high-precision timer int fps; // frames per second double mspf; // milliseconds per frame double dt; // constant game update rate double maxSkipFrames; // constant maximum of frames to skip in the update loop (important to not stall the system on slower computers)

void calculateFrameStatistics(); // computes frame statistics

// helper functions bool getPathToMyDocuments(); // stores the path to the My Documents folder in the appropriate member variable void createLoggingService(); // creates the file logger and registers it as a service bool checkConfigurationFile(); // checks for valid configuration file

protected: // application window HINSTANCE appInstance; // handle to an instance of the application Window* appWindow; // the application window (i.e. game window)

// game state bool isPaused; // true iff the game is paused

// constructor and destructor DirectXApp(HINSTANCE hInstance); ~DirectXApp();

// initialization and shutdown virtual util::Expected<void> init(); // initializes the DirectX application virtual void shutdown(util::Expected<void>* expected = NULL); // clean up and shutdown the DirectX application

// game loop virtual util::Expected<int> run(); // enters the main event loop void update(double deltaTime); // update the game world

// resize functions virtual void onResize(); // resize game graphics

// generating output virtual void render(double farseer); // renders the game world

// getters bool fileLoggerIsActive() { return activeFileLogger; } // returns true iff the file logger is active

public: friend class Window;};And here is the shiny new game loop!

util::Expected<int> DirectXApp::run(){ // reset (start) the timer timer->reset();

double accumulatedTime = 0.0; // stores the time accumulated by the rendered int nLoops = 0; // the number of completed loops while updating the game

// enter main event loop bool continueRunning = true; MSG msg = { 0 }; while(continueRunning) { // peek for messages while(PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg);

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT) continueRunning = false; }

// let the timer tick timer->tick();

if (!isPaused) { // compute fps calculateFrameStatistics();

// acquire input

// accumulate the elapsed time since the last frame accumulatedTime += timer->getDeltaTime();

// now update the game logic with fixed dt as often as possible nLoops = 0; while (accumulatedTime >= dt && nLoops < maxSkipFrames) { update(dt); accumulatedTime -= dt; nLoops++; }

// peek into the future and generate the output render(accumulatedTime / dt); } } return (int)msg.wParam;}The sourcode is available here.

Wow, we finally got to use some of our mathematical knowledge to explain game related stuff! Okay, to be honest, we elaborated on physics and the simulation of time and reality, but still, it was fun. There are still many open questions though, such as what happens when VSYNC fails, or how to implement a multithreaded game loop, but those questions are for a later time.

In the next tutorial, we will learn how to acquire keyboard and mouse input from Windows.

References

(in alphabetic order)

- Game Programming Algorithms and Techniques, by Sanjay Madhav

- Game Programming Patterns, by Robert Nystrom

- Introduction to 3D Game Programming with DirectX 11, by Frank D. Luna

- Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN)

- Tricks of the Windows Game Programming Gurus, by André LaMothe