One-Dimensional Kinematics

Between the idea and the reality, between the motion and the act, falls the shadow.

— T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men

The term kinematic is the English version of the French word cinématique, which is derived from the Greek κίνημα, or kinema, meaning motion, itself being derived from κινεῖν, or kinein, which means to move.

In this tutorial we will learn about one-dimensional kinematics, i.e., the motion on a straight line, of point particles. In the following, each time an object is mentioned, the object is thought of as a single point particle.

Distance and Displacement

To define movement, a coordinate system must be set up first. In all the basic tutorials, the entire action takes place

in the standard Euclidean plane

When objects move, they cover a certain distance, which is defined as the total length of travel, and measured

in metres (m). The displacement is defined as the change in position of an object over time, and also measured

in metres. Let

Imagine going to the computer store, which is, luckily, only

Defining the position of an object to be a mathematical function of time,

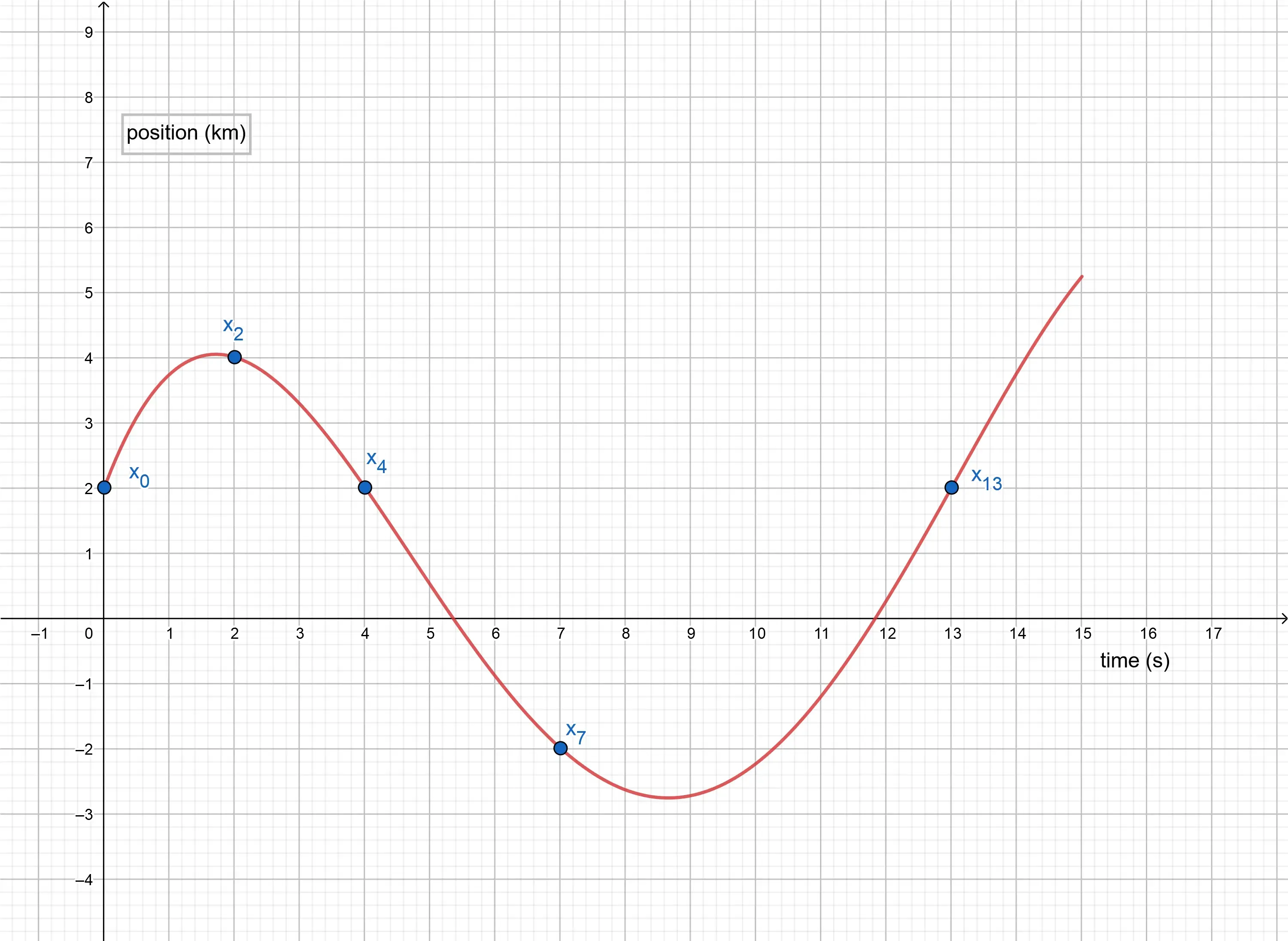

In the above graph one can see that while between

Average Speed and Velocity

Often it is not enough to know how far an object has travelled, but the time it took for the object to reach its

destination is important as well. This is called the average speed of an object. Let

Yet, even knowing the average speed of an object is frequently not satisfying enough. It is also essential to know how

fast an object was moving between certain points in time. This measure is called the average velocity of an object

and is defined as the displacement per time. Let

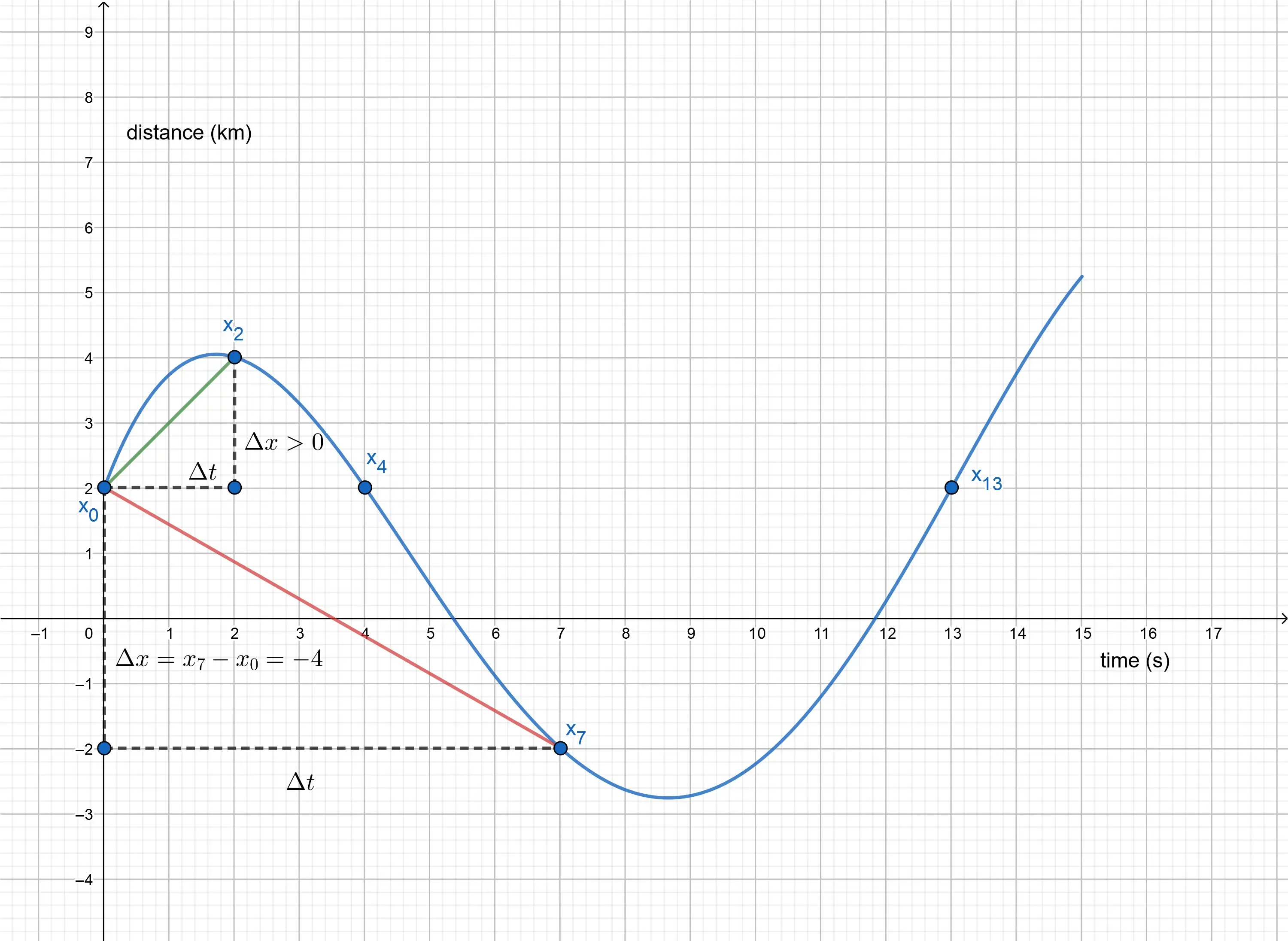

In the figure, one can also see that the slope of a line connecting two points is equal to the average velocity during that time interval.

Considering the velocity to be a mathematical function of time,

Instantaneous Velocity

Even the average velocity of an object does not hold enough information, as most often objects do not travel at the same

velocity all the time (just imagine driving a car) — their velocity changes constantly. It is ideally desirable to know

the velocity of an object at each instant of time (not only during certain time intervals). This is called the *

instantaneous velocity*,

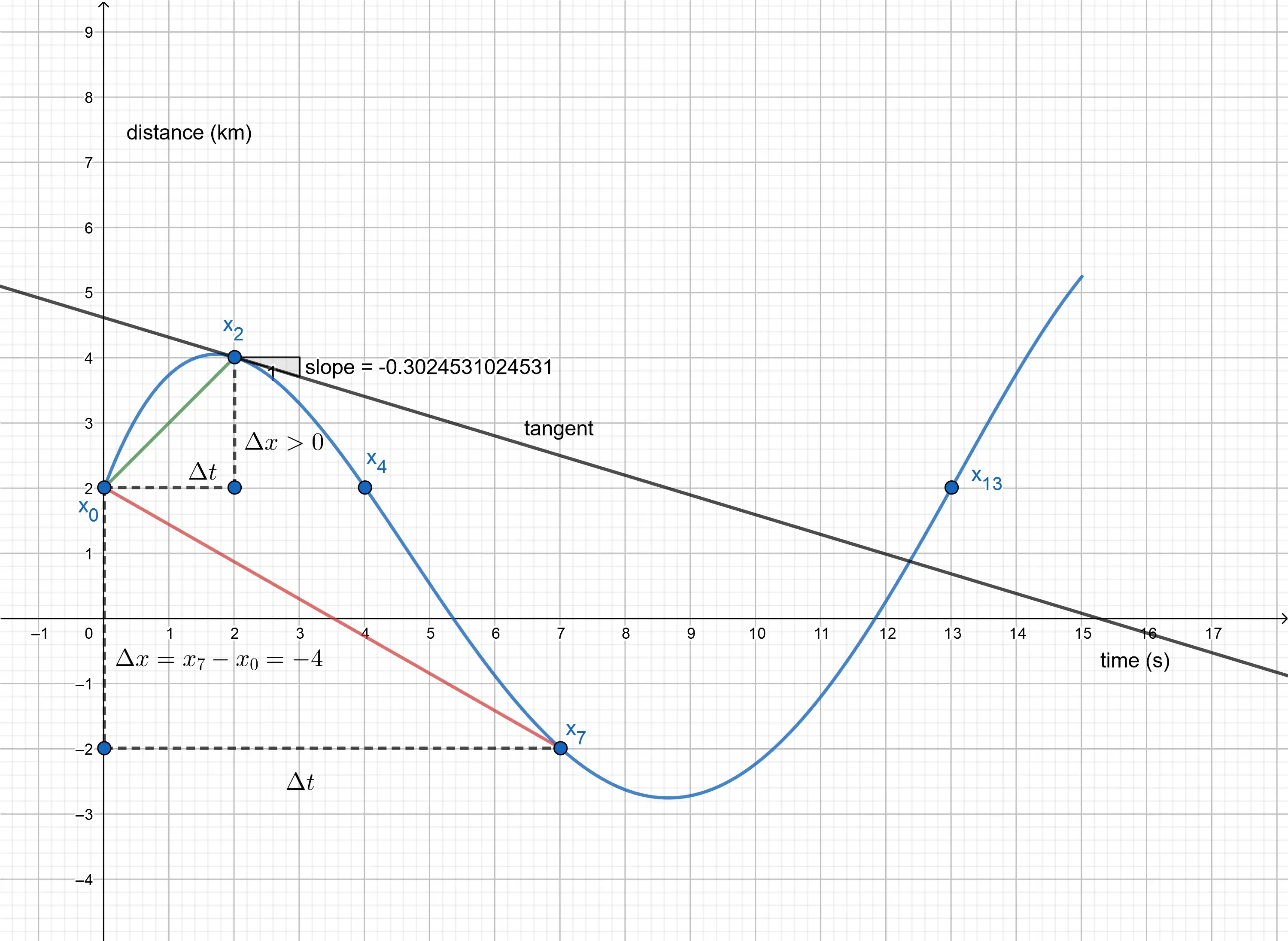

Geometrically, the instant velocity at the time

To be more precise, the instantaneous velocity of an object, at any particular moment in time, can be expressed as the

derivative of the position with respect to time:

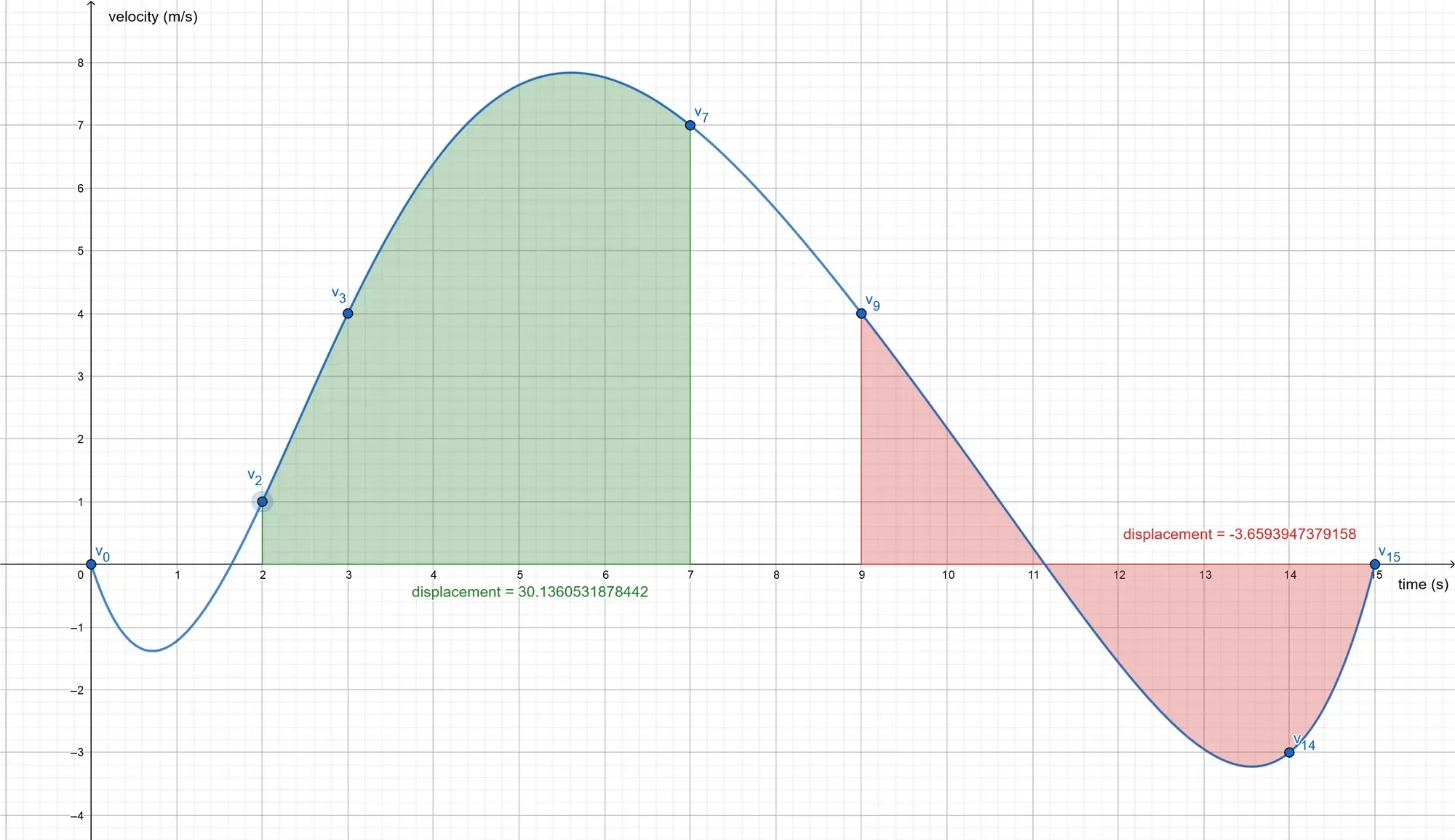

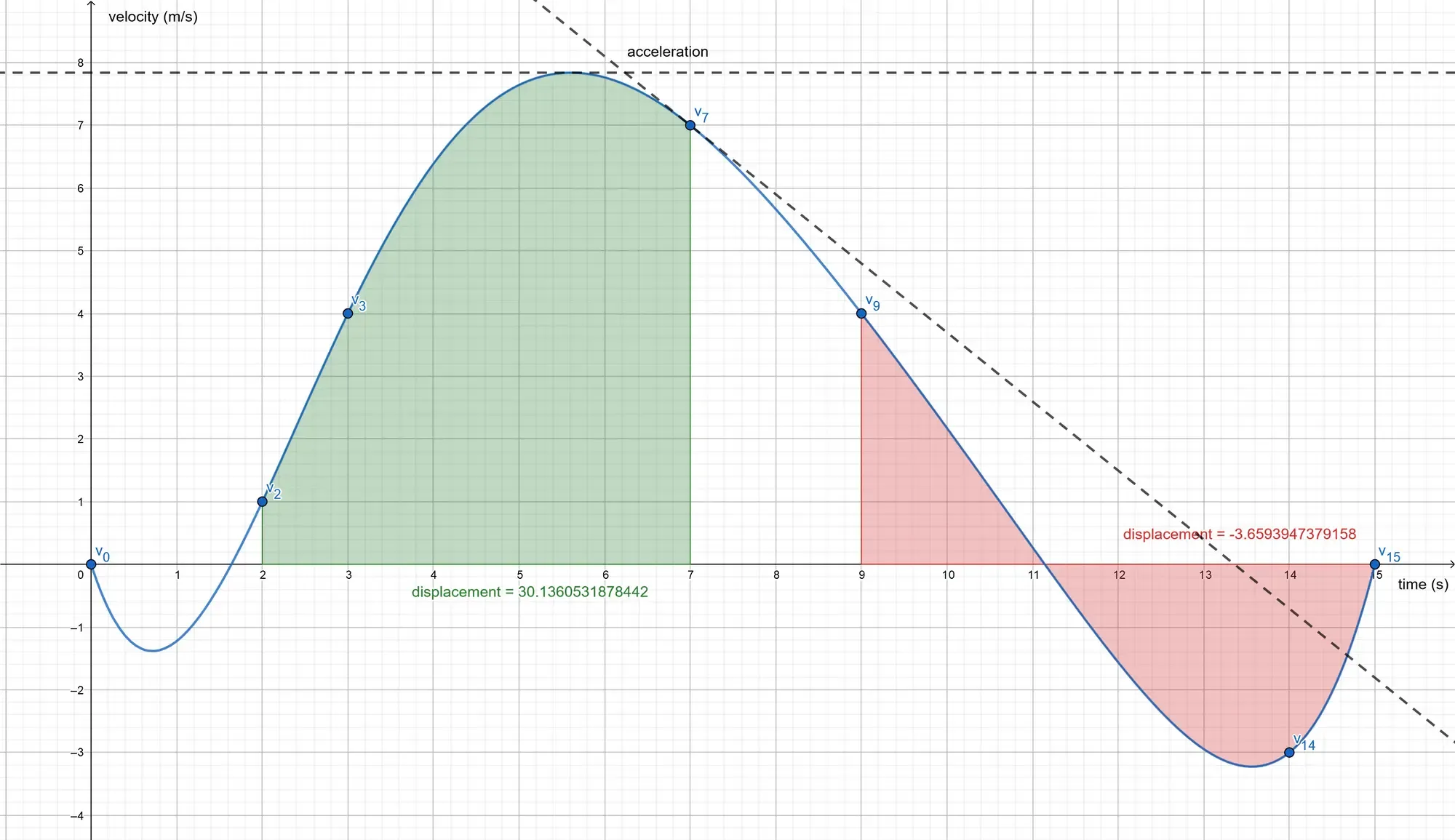

Drawing the graph of the velocity function, one can see that the displacement of an object can be expressed as the area

under the graph between two time points, or, the displacement function

A negative velocity simply means that the object is speeding ahead in the negative direction, as defined by the underlying vector space.

Between

Acceleration

As velocity describes the change of position over time, acceleration is the rate of change of velocity over time. The concept of acceleration is one of the most important concepts in classical physics. In later chapters we will learn that Galileo showed that falling bodies move with constant acceleration and how Newton managed to find a relation between acceleration and force. It is thus essential to have a good understanding of the concept of acceleration.

The average acceleration is defined analogously to the average velocity. Let

Similarly to the instantaneous velocity, the instantaneous acceleration,

Note that, in one dimension, if the velocity and the acceleration of an object have the same sign, the speed of the object increases. When the velocity and the acceleration have opposite signs, the speed of the object decreases.

To be mathematically more precise, the instantaneous acceleration at a point in time is defined as the derivative of

velocity with respect to time:

The figure above shows the acceleration as the slope of the tangent at a specific point. One can see that at the peak of

its velocity, the object has no acceleration for a brief moment of time (tangent line parallel to the

Motion with Uniform Acceleration

In the case of uniform or constant acceleration, it is relatively easy to derive simple formulas to describe the motion of an object. In an idealized world, without friction, for example, motion with constant acceleration can be used to model a wide range of everyday phenomena.

If an object has constant acceleration, its average and instantaneous accelerations are obviously the same. Let

The next question to ask is how far an object moves in a given time. Using the same simplification as above, the formula

of the average velocity reduces to

Finally, substituting

Implementing motion with uniform acceleration in C++ is now straightforward:

float Kinematics::posUM(const float x0, const float v0, const float a, float dt){ return x0 + v0 * dt + 0.5f * a * dt * dt;}Free Fall

Free fall, the motion of an object falling freely under the influence of gravity and gravity alone, is probably the most

famous example of motion with constant gravity. Galileo was most likely

the first to postulate that falling bodies moved with constant acceleration. The acceleration produced by the gravity,

Hamiltonian Systems and Symplectic Integration

As stated above, the problem of an object in motion is a classical mechanical problem. Recall that

By the year 1833, Sir William Hamilton had invented a new theory to reformulate those classical mechanical problems in a more modern way, providing a more abstract understanding of the theory. The main advantage of this new theory comes from the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian systems.

Newton’s equation of motion takes the form:

The equations of motion take this form if the Hamiltonian is of the form

The goal of this tutorial is not to give an introduction into Hamiltonian Systems, but rather to solve the equations of

motion, thus, given the initial conditions

Numerical Integration and Implementation

To algorithmically, or numerically, solve the above system of differential equations, the equations of motion, a technique called numerical integration is used. Numerical integration basically repeats certain small steps again and again, i.e., in this case, objects start at an initial position with an initial velocity and then, using small-time steps, the new velocity and position are computed, which are then set as the new initial positions and velocities. Thus, numerical integration tries to find an approximate discrete solution to a continuous problem by iteration.

One such approximate discrete solution of the Hamiltonian equations of motion can be produced by iterating

This technique is called semi-implicit Euler integration,

named after the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. This integration

technique is a symplectic integrator, which means it is well

suited to solve Hamiltonian systems, i.e. it also conserves the symplectic form

Note that to compute the position of the object at the time

After all that scary talk about abstract mathematics, implementing the semi-implicit Euler method to solve the equations of motions is actually straightforward:

void Kinematics::semiImplicitEuler(float& pos, float& vel, const float acc, const float dt){ vel += acc * dt; pos += vel * dt;}As an example, assume that nine bullets are shot from guns positioned at the left of the screen. The initial positions

of the centres of the bullets are stored in an array called centres, the initial velocities are stored in the

velocities array and the accelerations in the accelerations array. The motion of the bullets can then be modelled as

follows, just please note that in a game, the position, and velocity are obviously measured in pixels, or pixels per

second, instead of meters and meters per second: 1 pixel usually corresponds to about

const float Kinematics::metersPerPixel = 0.000264583f; // 1 pixel = 0.000264583 meters

util::Expected<void> PlayState::update(const double deltaTime){ if (isPaused) return { };

// get meters per pixel const float mpp = physics::Kinematics::metersPerPixel;

// update position based on symplectic integration of the equations of motion for (unsigned int i = 0; i < centers.size(); i++) { // the "even" bullets move with non-constant acceleration if (i % 2 != 0) accelerations[i] += rand()%10 * mpp;

// symplectic integrator: semi-implicit Euler physics::Kinematics::semiImplicitEuler(centers[i].x, velocities[i], accelerations[i], deltaTime);

// wrap screen if (centres[i].x > dxApp.getGraphicsComponent().getCurrentWidth()) { centres[i].x = 0.0f; accelerations[i] = rand()%10 * mpp; velocities[i] = rand()%100 * mpp; } }

// return success return { };}

util::Expected<void> PlayState::render(const double farSeer){ // let the far seer update the positions if necessary for (unsigned int i = 0; i < centers.size(); i++) centers[i].x += velocities[i]*farSeer;

// render circles for (unsigned int i = 0; i < centers.size(); i++) dxApp.getGraphicsComponent().get2DComponent().drawEllipse(centers[i].x, centers[i].y, 10.0f, 2.5f);

// print FPS information dxApp.getGraphicsComponent().getWriteComponent().printFPS();

// return success return { };}

That’s it. All in all, one-dimensional kinematics are rather easy to handle, but the theory behind Hamiltonian systems and symplectic integrators can be a bit intimidating. Just remember to update the velocity before updating the position, and you are all set!

References

- Dynamical Systems, Prof. Dr. K.-F. Siburg

- Dynamical Systems, C. Robinson

- Geogebra

- Physics, by James S. Walker

- Tricks of the Windows Programming Gurus, by A. LaMothe

- Wikipedia