A Windows Application

A window - it’s more entertaining than TV. Just ask a cat looking out, or a man looking in on a life he desires.

— Jarod Kintz, This Book is Not FOR SALE

Even though the goal of these tutorials is to write games that run on Windows, no advanced knowledge about actual Windows programming is necessary. All that needs to be done is to write a basic Windows program that opens a window, processes messages and calls the main game loop. That’s it.

Thus, to create a fully functional Windows program, five tasks must be completed (clearly

- Create a Window class.

- Create an event handler or WinProc.

- Register the Window class with Windows.

- Create an actual window from the previously created Window class.

- Create a main event loop that retrieves and dispatches Windows messages to the event handler.

Just imagine the snake being Windows. Now, with this in mind, the first goal is to learn how to create and open a window. A window is nothing more than a workspace that displays information, such as text and graphics, that the user can interact with. To work with windows, Windows offers a Window class:

Creating a Window class

Simply put, a Window class is a structure used by Windows to handle properties and actions of, surprise, a window. The first step to take when creating a window, is to define its properties by filling out the above-mentioned WNDCLASSEX structure:

typedef struct _WNDCLASSEX{ UINT cbSize; // size of this structure UINT style; // style flags WNDPROC lpfnWndProc; // function pointer to handler int cbClsExtra; // extra class info int cbWndExtra; // extra window info HANDLE hInstance; // the instance of the application HICON hIcon; // the main icon HCURSOR hCursor; // the cursor for the window HBRUSH hbrBackground; // the background brush to paint the window LPCTSTR lpszMenuName; // the name of the menu to attach LPCTSTR lpszClassName;// the name of the class itself HICON hIconSm; // the handle of the small icon} WNDCLASSEX;UINT cbSize

The first field, cbSize, holds the size of the WNDCLASSEX structure itself. If this structure is passed as a pointer, the receiver can always check the first field to decide how long the data chunk will be at the very least, and thus the class size does not need to be computed during runtime. Obviously, this flag can simply be set by using the sizeof operator.

UINT style

This member stores the desired style of the window. There are plenty of options available, but the most useful for now are CS_HREDRAW and CS_VREDRAW. Those tell Windows to redraw the window whenever it is moved vertically or horizontally. Please note that while that behaviour is useful for a window, but not for a fullscreen application like a game, fullscreen-applications won’t be considered in this tutorial until a more profound understanding of this entire Windows and DirectX business is acquired. For a list of all available style options, check the MSDN.

WNDPROC lpfnWndProc

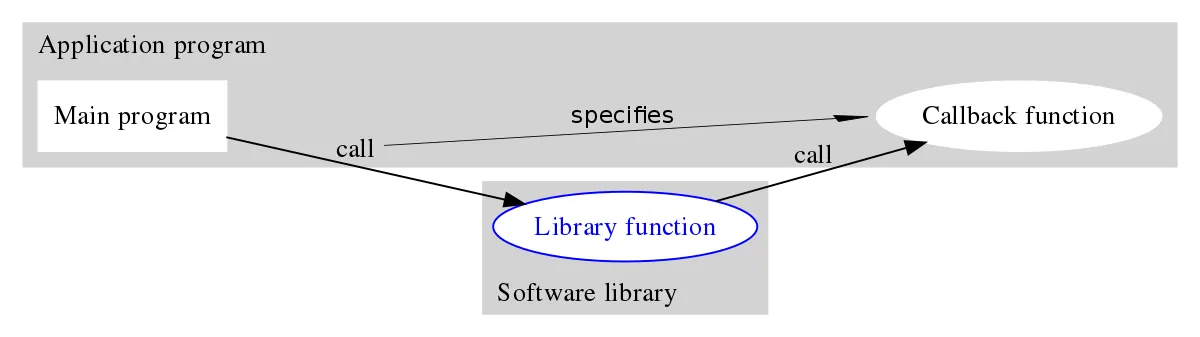

The next field of the WNDCLASSEX structure, lpfnWndProc, is a long function pointer to an event handler. Each Window class needs a callback function, that is, a function that handles events such as the window being moved or resized. This topic will be covered in detail in a few moments, and we will learn more about handling events in the next tutorial.

int cbClsExtra and cint bWndExtra

Those two members were originally designed to hold extra runtime information. However, most people do not use these fields at all and simply set them to 0. In this tutorial, we will simply do that as well.

HINSTANCE hInstance

This member is a handle to an instance of the application creating the window; this can simply be set to the value designated by Windows in the WinMain() function.

HICON hIcon

The next field sets the icon that will represent the application. For now, it is easiest to just use a standard icon. The LoadIcon() function retrieves a handle to a common icon. Creating and loading a custom icon will be briefly covered in a later tutorial.

HCURSOR hCursor

This is similar to hIcon in that it is a handle to a graphics object, namely the mouse cursor. Again, for now, it is easiest to just use a standard mouse cursor. The LoadCursor() function retrieves a handle to a common cursor. Creating and loading a custom cursor will be briefly covered in a later tutorial.

HBRUSH hbrBackground

Whenever a window is changed, Windows repaints the background of the window’s client area with a predefined colour, using a brush. Obviously, hbrBackground is a handle to the brush object that our window wants to be refreshed with. Requesting a basic system brush is done by calling the GetStockObject() function.

LPCTSTR lpszMenuName

This is a long pointer to a null-terminated constant string of the name of a menu resource to load and attach to the window. This is not really used for modern games, and thus it will be set to NULL in this tutorial. Note that later on, much later, this will come handy when creating development tools such as map or asset editors.

LPCTSTR lpszClassName

Filled with a long pointer to a null-terminated constant string, this member is used to identify a specific window class structure. This is only useful if an application opens more than one window; Windows then needs to be able to monitor which window is supposed to do what.

HICON hIconSm

This is a handle to the icon displayed on the Windows title bar and the desktop taskbar. For now, it is easiest to just use a standard icon. The LoadIcon() function retrieves a handle to a common icon. Creating and loading a small custom icon will be briefly covered in a later tutorial.

Registering the Windows Class

Now that the window specifications are fully defined as desired, the RegisterClassEx() function can be used to register the window class to Windows, that is, to simply tell Windows about the newly designed class, as follows:

WNDCLASSEX wc;wc.cbClsExtra = 0; // no extra bytes neededwc.cbSize = sizeof(WNDCLASSEX); // size of the window description structurewc.cbWndExtra = 0; // no extra bytes neededwc.hbrBackground = (HBRUSH)GetStockObject(NULL_BRUSH); // brush to repaint the background withwc.hCursor = LoadCursor(0, IDC_ARROW); // load the standard arrow cursorwc.hIcon = LoadIcon(0, IDI_APPLICATION); // load the standard application iconwc.hIconSm = LoadIcon(0, IDI_APPLICATION); // load the standard small application iconwc.hInstance = dxApp->appInstance; // handle to the core application instancewc.lpfnWndProc = mainWndProc; // window procedure functionwc.lpszClassName = L"bell0window"; // class namewc.lpszMenuName = 0; // no menuwc.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW; // send WM_SIZE message when either the height or the width of the client area are changed

// register the windowif (!RegisterClassEx(&wc)) return std::invalid_argument("The window class could not be registered; most probably due to invalid arguments!");If the registration succeeds, the return value is a class atom that uniquely identifies the class being registered. If the function fails, the return value is zero. And please note that all window classes that an application registers are unregistered when it terminates, no manual cleaning is necessary.

Creating the Window

Now that Windows knows about the specifics of the window, it can finally be created with a call to the CreateWindowEx() function:

HWND CreateWindowEx(DWORD dwExStyle, // extended window styleLPCTSTR lpClassName, // pointer to registered class nameLPCTSTR lpWindowName,// pointer to window nameDWORD dwStyle, // window styleint x, // horizontal position of windowint y, // vertical position of windowint nWidth, // window widthint nHeight, // window heightHWND hWndParent, // handle to parent or owner windowHMENU hMenu, // handle to menu, or child-window identifierHINSTANCE hInstance, // handle to application instanceLPVOID lpParam); // pointer to window-creation dataThe CreateWindowEx() function returns a handle to the newly created window, or NULL, if some error occurred.

Here comes a brief description of the parameters of the function.

DWORD dwExStyle

For games, this can be set to NULL. Check the corresponding MSDN page. For now, we set this to WS_EX_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW (see below for an explanation).

LPCTSTR lpClassName

This is a long pointer to a constant string to the name of the windows class to be created. In this tutorial, that would be Lbell0window class.

LPCTSTR lpWindowName

This long pointer to a null-terminated constant string contains the name, or the title, of the window.

DWORD dwStyle

This flag describes what the window will look like and how it will behave. In this tutorial, we will set the style to WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW: An overlapped window has a title bar and a border. Check the MSDN for all the possible values.

int x, int y

Those two parameters hold the position of the upper left-hand corner of the window in pixel coordinates. Simply use CW_USEDEFAULT if the actual location is of no importance (which is most often the case).

int nWidth, int nHeight

Those set the width and height of the window in pixels. Once again, if the initial dimensions are unimportant, CW_USEDEFAULT can be used.

HWND hWndParent

This parameter takes a handle to the parent window. If there is no parent, setting this to NULL designates the desktop to be the parent for this window.

HMENU hMenu

This is the handle to the menu to attach to the window. For now, this will be NULL.

HINSTANCE hInstance

This parameter is the handle to the instance of the application creating the window. This can be set by using the HINSTANCE from the WinMain() function.

LPVOID lpParam

This is advanced and not needed for the purposes of this tutorial, thus it will be set to NULL.

Now the time has finally come to actually create the window!

// create the windowmainWindow = CreateWindowEx(WS_EX_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, wc.lpszClassName, L"bell0window", WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, NULL, NULL, dxApp->appInstance, NULL);if (!mainWindow) return std::invalid_argument("The window could not be created; most probably due to invalid arguments!");

// show and update the windowsShowWindow(mainWindow, SW_SHOW);UpdateWindow(mainWindow);

// log and return successutil::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The main window was successfully created."); return {};The ShowWindow function controls how the window is to be shown. The first parameter takes the handle to the window and the second parameter controls how the window is to be shown: SW_SHOW, for example, activates the window and displays it in its current size and position.

With a call to the UpdateWindow function Windows is forced to update a window’s (specified by a handle to the window) contents, which generates a WM_PAINT message that needs to be handled by the event handler.

Now that four of the five tasks have been completed successfully, it is time to tackle the infamous event handler.

Event Handler

The event handler is a callback function called by Windows from the main event loop of the system whenever an event occurs that a running window must handle. A callback is an executable code that is passed as an argument to another code, which is then expected to execute (call back) the argument at some convenient time.

An application only needs to do something about events when Windows tells it so. Otherwise, it can just continue doing whatever it is supposed to do, until Windows calls in again. A window can handle as many, or as few, events as desired and pass all other events to the default Windows event handler — please note that the fewer events it handles, the faster an application can go back to the chores it was meant to do.

To get a working window, only very few messages have to be handled; Windows will take care of all the dirty work. Thank you, Windows!

The prototype of such an event handler function, also called a Window Procedure, is small enough:

LRESULT CALLBACK WindowProc(HWND hwnd, // window handle of senderUINT msg, // the message idWPARAM wParam, // further defines messageLPARAM lParam);// further defines messageHWND hwnd

This is a handle to the current window and only really useful when dealing with multiple windows. The event handler needs, or wants, to know which messages are coming from which window.

UINT msg

The ID of the actual message that must be handled. For a list of system-defined messages, check the MSDN.

WPARAM wParam and LPARAM lParam

Those contain additional information about the message. The exact information stored in those parameters depends on what message was sent.

Handling messages is actually quite easy. When Windows passes a message, that message is placed in an event queue. The GetMessage() or PeekMessage() functions can be used to retrieve that message from the queue. The TranslateMessage() function then translates virtual-key messages into character messages and finally the DispatchMessage() function dispatches the message to the window procedure function, which then, in turn, selects the appropriate measures to deal with the event.

What most people do is to simply switch on the message and to then write code for each specific case. Based on the actual message, it will be clear whether a further evaluation of the wParam and lParam parameters is needed. Don’t worry if all of this sounds confusing, it will get apparent once we see a few examples.

For now, let us have a look at some of the possible messages that Windows might send our way (as always, also check the MSDN for more information).

- WM_ACTIVATE: sent when a window is activated (or focused).

- WM_CLOSE: sent when a window is closed.

- WM_CREATE: sent when a window is first created.

- WM_DESTROY: sent when a window is destroyed.

- WM_MOVE: sent when a window has been moved.

- WM_MOUSEMOVE: sent when the mouse has been moved.

- WM_KEYUP: sent when a key is released.

- WM_KEYDOWN: sent when a key is pressed.

- WM_PAINT: sent when a window needs repainting.

- WM_QUIT: sent when the application is terminating.

- WM_SIZE: sent when a window changes size.

- WM_MENUCHAR: sent when a menu is active and the user presses a key that does not correspond to any mnemonic or accelerator key.

- WM_MINMAXINFO: sent when the size or position of the window is about to change.

And here is a minimal example for a window procedure function. As we progress with the tutorials, more functionality will be added.

LRESULT CALLBACK Window::msgProc(HWND hWnd, unsigned int msg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam){ switch (msg) {

case WM_DESTROY: // window is flagged to be destroyed: send a quit message util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The main window was flagged for destruction."); PostQuitMessage(0); return 0; }

// let Windows handle other messages return DefWindowProc(hWnd, msg, wParam, lParam);}WM_DESTROY

When the window is flagged to be destroyed, we send a PostQuitMessage(0) to indicate to the system that we want to terminate our application (since we only have one window). Basically, this puts a WM_QUIT message in the message queue, which at some point causes the main event loop to bail.

After having processed the WM_DESTROY message, it is advised to return

DefWindowProc

It is crucial to not lose unhandled messages. This is done using the passthrough function DefaultWindowProc, which simply passes unhandled messages onto the Windows message queue for default processing.

The Main Loop

As seen above, there are two functions to check whether there are messages in the message queue, GetMessage() and PeekMessage().

Using GetMessage, once the window is created, it goes into the main event loop, where the GetMessage function actually waits for a message. This is obviously not acceptable for a game that is aiming at delivering 30 frames per second, at least; There is no time to wait for messages.

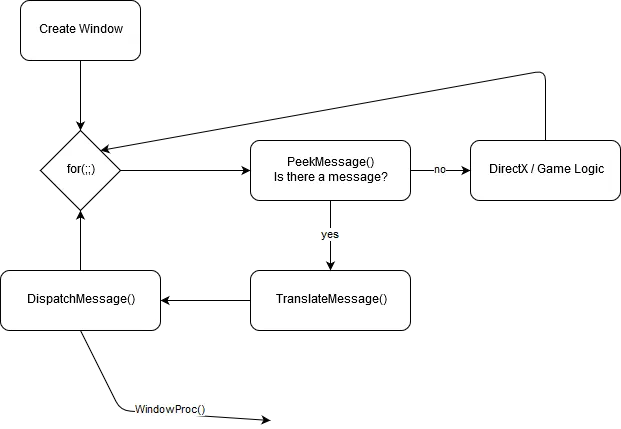

This is where the PeekMessage() function comes into play. It does not wait for a message, as depicted in the following diagram:

PeekMessage does essentially the same as GetMessage, but with one vital difference: If there is no message in the queue, it allows the application to continue until there actually is an event that must be handled.

Here is the definition of PeekMessage:

BOOL PeekMessage( LPMSG lpMsg, // pointer to message structure HWND hWnd, // handle to window UINT wMsgFilterMin, // first message UINT wMsgFilterMax, // last message UINT wRemoveMsg); // removal flagsWhat do those parameters mean?

LPMSG lpMsg

This is a pointer to a message structure that receives message information. This is the message we switch on in the game loop.

HWND hWnd

A handle to the window whose messages are to be retrieved. If hWnd is NULL, PeekMessage retrieves messages for any window that belongs to the current thread.

UINT wMsgFilterMin and UINT wMsgFilterMax

With those parameters, a range filter for messages can be set up. If wMsgFilterMin and wMsgFilterMax are both zero, PeekMessage returns all available messages.

UINT wRemoveMsg

This flag specifies how messages are to be handled. There are two interesting options for us here:

- PM_NOREMOVE: messages are not removed from the queue after processing by PeekMessage.

- PM_REMOVE: messages are removed from the queue after processing by PeekMessage.

There are thus two options to use PeekMessage. The first option being to call PeekMessage with PM_NOREMOVE to see if a message is in the queue, and to then call GetMessage to retrieve it. The second and preferred option would be to use PM_REMOVE and use PeekMessage to retrieve the messages itself.

Now we finally have all the knowledge we need to tackle our last task: Creating a real-time game loop!

Many authors, as well as many online tutorials, propose the following game loop:

util::Expected<int> DirectXApp::run(){ MSG msg = { 0 };

// enter main event loop while (msg.message != WM_QUIT) { // peek for messages if (PeekMessage(&msg, 0, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) //appWindow->mainWindow { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg); } else { // run game logic } } return (int)msg.wParam;}Unfortunately, this game loop is, at least in my opinion, actually badly designed.

I just can’t get my head around this if — else flow. If there was a message, the game logic is not updated and that somehow makes no sense. One might even ask why the game gets a chance to run at all (a new message might have appeared each time PeekMessage got active), but let us think for a moment: The key idea here is that the message processing will run much faster than the rate at which messages are sent.

Let

So the if-part of the game loop will process the message in at most

While this explains why this loop doesn’t prevent the game from running normally, I am by now convinced that it is a bad design choice.

A much more natural game loop would look like this:

util::Expected<int> DirectXApp::run(){ MSG msg = { 0 }; // enter main event loop for(;;) { // peek for messages while (PeekMessage(&msg, 0, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg); }

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT) break;

// update the game logic } return (int)msg.wParam;}This game loop processes all messages on the queue and then lets the game run, assuming it is not yet time to quit. PeekMessage should only dispatch the WM_QUIT message once the message queue is empty, therefore the last message processed should indeed be WM_QUIT, but this is, unfortunately, not guaranteed. Nonetheless, this execution flow is much more explicit.

We can still make sure that the applications quits upon receiving a WM_QUIT message by adding a simple boolean:

util::Expected<int> DirectXApp::run(){ bool continueRunning = true; MSG msg = { 0 };

// enter main event loop while(continueRunning) { // peek for messages while (PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg);

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT) continueRunning = false; }

// run the game logic } return (int)msg.wParam;}And here we are. Our five tasks completed heroically, we are well on our way to becoming modern heroes of the computer age.

Putting it all together

To keep our project clean and tidy, I have created a DirectXApp class which, as you can guess, is the main class for a DirectX application, it coordinates all the other classes. For now, DirectXApp has a window (obviously the window we just created), which is an instance of a Window class. The window class handles everything related to our window, including the message procedure.

Download the source code to have a look at the architecture.

WinMain

int WINAPI WinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, HINSTANCE hPrevInstance, LPSTR lpCmdLine, int nShowCmd){ // try to start the logging service; if this fails, abort the application! try { startLoggingService(); } catch (std::runtime_error) { ... }

// create and initialize the game DirectXGame game(hInstance); util::Expected<void> gameInitialization = game.init();

// if the initialization was successful, run the game, else, try to clean up and exit the application if (gameInitialization.wasSuccessful()) { // initialization was successful -> run the game util::Expected<int> returnValue = game.run();

// clean up after the game has ended game.shutdown(&(util::Expected<void>)returnValue);

// gracefully return return returnValue.get(); } else { // a critical error occured during initialization, try to clean up and the print information about the error game.shutdown(&gameInitialization);

// humbly return with an error return -1; }}Game Class

class DirectXGame : core::DirectXApp{public: // constructor and destructor DirectXGame(HINSTANCE hInstance); ~DirectXGame();

// override virtual functions util::Expected<void> init() override; // game initialization void shutdown(util::Expected<void>* expected = NULL) override; // cleans up and shuts the game down (handles errors)

// run the game util::Expected<int> run();};// constructor and destructorDirectXGame::DirectXGame(HINSTANCE hInstance) : DirectXApp(hInstance){ }DirectXGame::~DirectXGame(){ }

// initialize the gameutil::Expected<void> DirectXGame::init(){ // initialize the core DirectX application util::Expected<void> applicationInitialization = DirectXApp::init(); if (!applicationInitialization.wasSuccessful()) return applicationInitialization;

// log and return success util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("Game initialization was successful."); return {};}

// run the gameutil::Expected<int> DirectXGame::run(){ // run the core DirectX application return DirectXApp::run();}

// shutdownvoid DirectXGame::shutdown(util::Expected<void>* expected){ // check for error message if (expected != NULL && !expected->isValid()) { // the game was shutdown by an error // try to clean up and log the error message try { // do clean up

// throw error expected->get(); } catch (std::exception& e) { // create and print error message string std::stringstream errorMessage; errorMessage << "The game is shutting down with a critical error: " << e.what(); util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::error>(std::stringstream(errorMessage.str())); return; } }

// no error: clean up and shut down normally util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The game was shut down successfully.");}DirectX App

class DirectXApp{protected: // application window HINSTANCE appInstance; // handle to an instance of the application Window* appWindow; // the application window (i.e. game window)

// constructor and destructor DirectXApp(HINSTANCE hInstance); ~DirectXApp();

util::Expected<int> run(); // enters the main event loop

// virtual methods, must be overriden virtual util::Expected<void> init(); // initializes the DirectX application virtual void shutdown(util::Expected<void>* expected = NULL); // clean up and shutdown the DirectX application

public: friend class Window;};DirectXApp::DirectXApp(HINSTANCE hInstance) : appInstance(hInstance), appWindow(NULL) { }DirectXApp::~DirectXApp(){ shutdown();}

util::Expected<void> DirectXApp::init(){ // create the application window try { appWindow = new Window(this); } catch (std::runtime_error) { return std::runtime_error("DirectXApp was unable to create the main window!"); }

// log and return success util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The DirectX application initialization was successful."); return {};}

void DirectXApp::shutdown(util::Expected<void>* expected){ if (appWindow) delete appWindow;

if (appInstance) appInstance = NULL;

util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The DirectX application was shutdown successfully.");}

util::Expected<int> DirectXApp::run(){ bool continueRunning = true; MSG msg = { 0 };

// enter main event loop while(continueRunning) { // peek for messages while (PeekMessage(&msg, NULL, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) { TranslateMessage(&msg); DispatchMessage(&msg);

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT) continueRunning = false; }

// run the game logic } return (int)msg.wParam;}Window

class Window{private: HWND mainWindow; // handle to the main window DirectXApp* dxApp; // the core application class

util::Expected<void> init(); // initializes the window

public: // constructor and destructor Window(DirectXApp* dxApp); ~Window();

// getters inline HWND getMainWindowHandle() { return mainWindow; };

// the call back function virtual LRESULT CALLBACK msgProc(HWND hWnd, unsigned int msg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam);

friend class DirectXApp;};Window::Window(DirectXApp* dxApp) : mainWindow(NULL), dxApp(dxApp){ // this is necessary to forward messages window = this;

// initialize the window util::Expected<void> rv = this->init(); if (!rv.isValid()) { // log the error try { rv.get(); } catch (std::exception& e) { // create and print error message string std::stringstream errorMessage; errorMessage << "Creation of the game window failed with: " << e.what(); util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::error>(std::stringstream(errorMessage.str()));

// throw an error throw std::runtime_error("Window creation failed!"); } }}

Window::~Window(){ if (mainWindow) mainWindow = NULL;

if (dxApp) dxApp = NULL;

// log util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("Main window class destruction was successful.");}

util::Expected<void> Window::init(){ // specify the window class description WNDCLASSEX wc;

// white window wc.cbClsExtra = 0; // no extra bytes needed wc.cbSize = sizeof(WNDCLASSEX); // size of the window description structure wc.cbWndExtra = 0; // no extra bytes needed wc.hbrBackground = (HBRUSH)GetStockObject(NULL_BRUSH); // brush to repaint the background with wc.hCursor = LoadCursor(0, IDC_ARROW); // load the standard arrow cursor wc.hIcon = LoadIcon(0, IDI_APPLICATION); // load the standard application icon wc.hIconSm = LoadIcon(0, IDI_APPLICATION); // load the standard small application icon wc.hInstance = dxApp->appInstance; // handle to the core application instance wc.lpfnWndProc = mainWndProc; // window procedure function wc.lpszClassName = L"bell0window"; // class name wc.lpszMenuName = 0; // no menu wc.style = CS_HREDRAW | CS_VREDRAW; // send WM_SIZE message when either the height or the width of the client area are changed

// register the window if (!RegisterClassEx(&wc)) return std::invalid_argument("The window class could not be registered; most probably due to invalid arguments!");

// create the window mainWindow = CreateWindowEx(WS_EX_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, wc.lpszClassName, L"bell0window", WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, NULL, NULL, dxApp->appInstance, NULL); if (!mainWindow) return std::invalid_argument("The window could not be created; most probably due to invalid arguments!");

// show and update the windows ShowWindow(mainWindow, SW_SHOW); UpdateWindow(mainWindow);

// log and return success util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The main window was successfully created."); return {};}

LRESULT CALLBACK Window::msgProc(HWND hWnd, unsigned int msg, WPARAM wParam, LPARAM lParam){ switch (msg) {

case WM_DESTROY: // window is flagged to be destroyed: send a quit message util::ServiceLocator::getFileLogger()->print<util::SeverityType::info>("The main window was flagged for destruction."); PostQuitMessage(0); return 0; }

// let Windows handle other messages return DefWindowProc(hWnd, msg, wParam, lParam);}Now bask in the glory that is an empty window — truly a Herculean feat!

And here is the produced log file:

0: 7/7/2017 23:5:53 INFO: mainThread: The file logger was created successfully.1: 7/7/2017 23:5:53 INFO: mainThread: The main window was successfully created.2: 7/7/2017 23:5:53 INFO: mainThread: The DirectX application initialization was successful.3: 7/7/2017 23:5:53 INFO: mainThread: Game initialization was successful.4: 7/7/2017 23:5:54 INFO: mainThread: The main window was flagged for destruction.5: 7/7/2017 23:5:54 INFO: mainThread: The game was shut down successfully.6: 7/7/2017 23:5:54 INFO: mainThread: Main window class destruction was successful.7: 7/7/2017 23:5:54 INFO: mainThread: The DirectX application was shutdown successfully.8: 7/7/2017 23:5:54 INFO: mainThread: The file logger was destroyed.Exercise

Why does the window not get redrawn when it is resized? Why does the computer slow down so dramatically? How can we fix that?

Solution

So what went wrong in this tutorial, why doesn’t the window behave as expected when being resized? Well actually it does behave as expected; we passed the NULL_BRUSH during registration, that means whenever the window is resized, Windows tries to paint it, but it has no brush! Thus, the window does not get repainted and eventually Windows will bombard us with WM_PAINT messages that we can’t fulfil and thus the entire system clogs.

The solution actually straightforward, simply use WHITE_BRUSH instead of NULL_BRUSH when defining the window properties:

wc.hbrBackground = (HBRUSH)GetStockObject(WHITE_BRUSH); // brush to repaint the background withGo ahead, try it out. Simply change that one line of code and enjoy a working white window to your heart’s content. Here is the corrected source code.

References

Literature

(in alphabetic order)

- Microsoft Developer Network

- Tricks of the Windows Game Programming Gurus, by André LaMothe

Art

- Draw.io

- Wikipedia