Newton's Laws of Motion

If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.

— Isaac Newton

All of us are proud of our freedom, yet we are all bound and have our very existence constrained and regulated by three fundamental, yet elementary, laws of physics: Newton’s Laws of Motion. Studying these laws is essential and allows going beyond the simple descriptions of motion, as seen in the previous tutorials, to actually study the causes of motion, called dynamics: Generally speaking, dynamics is the study of how a physical system develops, or alters over time, and why.

One example of how much of a powerful tool, Newtonian dynamics can be, was the prediction of the return date of a comet by Edmund Halley. While Newton’s Laws of Motion rule supreme when it comes to everyday phenomena, what follows in this tutorial is not the complete truth for objects moving near the speed of light and for objects comparable in size to atoms.

This tutorial just briefly introduces the three laws of motion. For a more mathematical introduction into the equation of motion, read the tutorial „Galileo versus Newton“.

Let

Mass and Force

Let’s begin the journey into Newtonian dynamics by covering two of the most important fundamental physical concepts: mass and force.

Mass

All matter has mass. Mass is both a property of a physical body and a measure of its resistance to acceleration when a force is applied to it. The mass of an object also determines the strength of its gravitational attraction to other bodies.

It is essential to note that mass is different from the weight of an object. An often occurring misconception is that

people say that they weigh, for example, 70 kg. The first thing to notice is that kilograms are not the metric measure

of weight, but that of mass. Weight is measured in Newton, abbreviated by N, and related to the mass of an object by the

following formula:

In the context of this tutorial, mass can be considered a measure of how difficult it is to change the velocity of an object — to get an object to start moving, if it is at rest, to stop its motion or to change its direction of motion, if it is already moving. As an early and easy example, imagine trying to stop a baseball that is coming right at you. Not too difficult, right? Now imagine trying to do the same with a car, racing at you at full speed? (Please don’t actually try this out!) Not so easy any more, right? I am sure you agree now that the car has a much greater mass than the baseball, it is quite simply a lot more challenging to alter the motion of the car, than that of the baseball.

Force

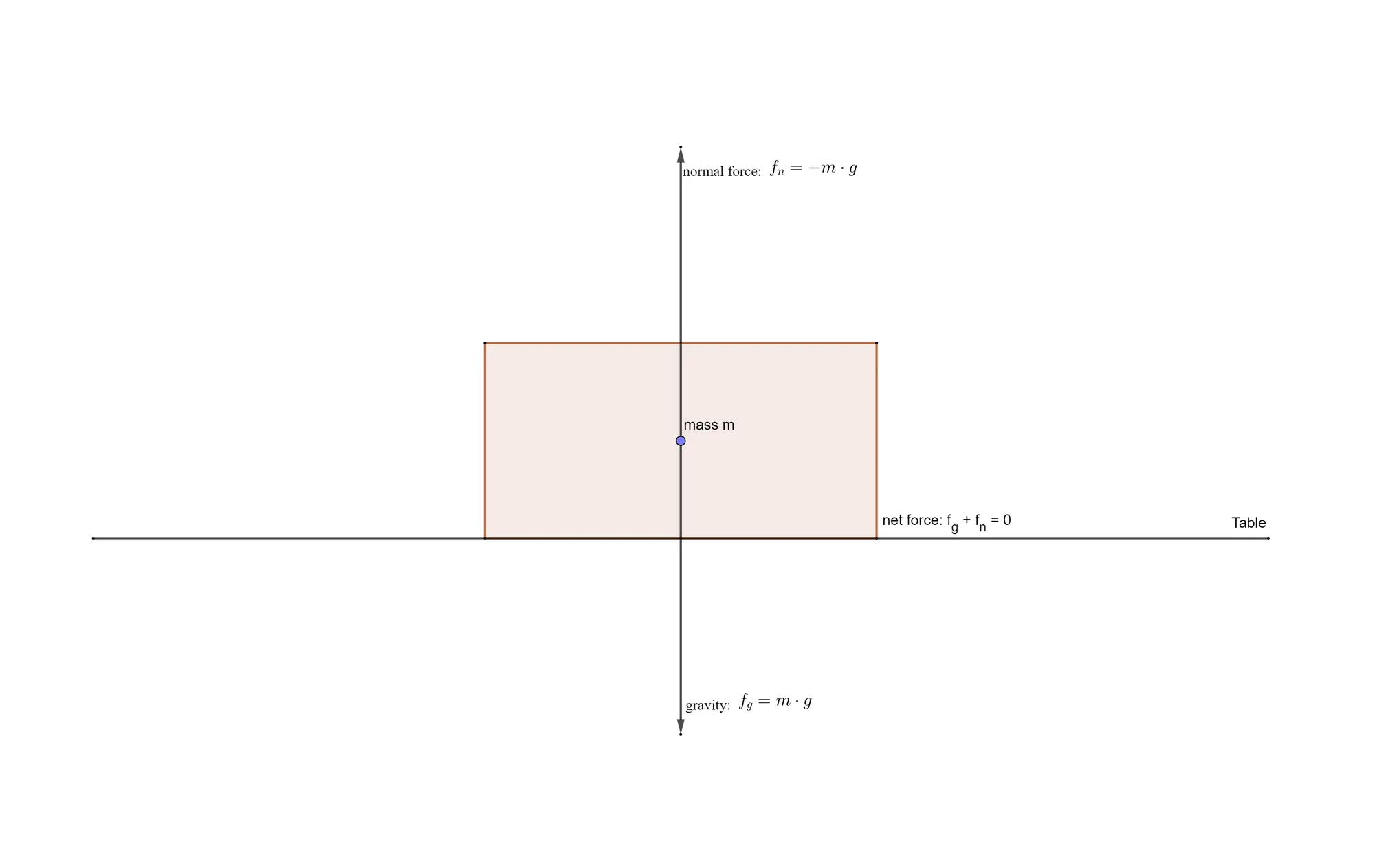

Undoubtedly, one of the most important concepts in physics is force. Simply put, a force is a push or a pull. As an easy example, just look at any object on your desk; a book, perhaps. Gravity is pulling the book towards the centre of the Earth, while the table is exerting an upwards force, making sure the book doesn’t disappear to China. Forces, and the mass of an object, are also why trying to pick up an object from the floor can cause some pain in the lower back of your body.

A force is a vectorial property: it has a direction and a norm, the magnitude of the force. In general, there are many forces acting upon an object at any given time. For example, the book on the table experiences a downward force due to gravity and an upward force due to the table. If it is pushed across the table, it also experiences a horizontal force. The total force, or net force, exerted on an object, is the vector sum of the individual forces acting on the object.

Force is measured in Newtons, abbreviated by N. One Newton is defined as the force required to give one kilogram of mass

an acceleration of

In video games, the concept of forces can be practical, when, for example, trying to apply artificial forces, like explosions, to game objects, and computing the resulting acceleration. Most importantly, though, a thorough understanding of dynamics is important to properly handle collisions.

Newton’s First Law of Motion

In his „Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica“, Newton states his First Law of Motion as follows:

Lex I: Corpus omne perseverare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare.

Translated to English, the law states:

Law I: Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.

This law was actually first enounced by Galileo, and is also known as the law of inertia, from the Latin word “iners“, meaning idle or sluggish. In other words, “Inertia” is thus the resistance, of any physical object, to any change or alteration in its velocity. An object is “sluggish” in the sense that, if at rest, it won’t start moving until “forced” to, and, if already moving, it won’t alter its speed or direction, unless a force causes the change. According to the law of inertia, being at rest and moving with constant velocity are actually the same state.

Mathematically, the law of inertia can be formulated using the derivative of the velocity, i.e. the acceleration. Let

the mass of an object be a non-zero constant, and let further

Just as an anecdotal note: It was a bit tricky to actually spot the law of inertia, as on the Earth’s surface, inertia is often masked by the evil head of friction and air resistance, which decrease the speed of moving objects. This misled the famous Greek philosopher Aristotle, among many others, to believe, that objects would move only as long as force was applied to them.

Inertial Frame of Reference

Imagine a pedestrian, standing still, watching a cargo train pass by with constant velocity. On one of the trailers, a worker sits next to his lunch box. From the point of view of the worker on the train, the lunch box has no net force acting upon it, and thus it is at rest. From the pedestrian’s perspective, the lunch box also has no net force acting upon it, and thus it continues to move with constant velocity. Actually, both people see the lunch box moving with constant velocity: that velocity just happens to be zero from the perspective of the worker sitting next to it. It is said that both observers are in an inertial frame of reference, that is, a frame of reference in which the law of inertia holds.

Such a frame of reference can simply be thought of as a coordinate system within an affine space. This allows for a more modern reformulation of the first Law of Motion: In an inertial frame of reference, an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by a force.

What happens when the train suddenly comes to a halt? Although from the perspective of the worker there is still no force acting upon the lunch box, the lunch box will fly around, in fact, it simply continues to move forward with the same velocity, while the train comes to a halt. While this is a perfectly normal behaviour from the pedestrian’s perspective, for the worker in the train it looks as if the lunch box had suddenly accelerated, which is a violation of Newton’s First Law of Motion. Clearly, his frame of reference was no longer inertial. In general, any frame that accelerates relative to an inertial frame is non-inertial.

Even though the surface of the Earth accelerates slightly, due to its rotational and orbital motions, that acceleration is so small, that the Earth’s surface can be considered an inertial frame of reference.

Galilean Invariance

In his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Galileo described that the laws of motion are the same in all inertial frames. Today, if two frames are inertial, they are called invariant, or, more precisely, Galilean invariant. Basically stating, the laws of motion are invariant under the choice of a coordinate-system for the affine space, i.e. forces and accelerations are invariant under the choice of coordinate systems.

For a more thorough introduction into space-time, inertial frames and Galilean Invariance, read the tutorial called Galileo versus Newton.

Newton’s Second Law of Motion

The following is the second law of motion as stated in the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica:

Lex II: Mutationem motus proportionalem esse vi motrici impressae, et fieri secundum lineam rectam qua vis illa imprimitur.

Translated to English, that means:

Law II: The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impress’d; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impress’d.

Basically speaking, the second law of motion states that unbalanced forces cause accelerations directly proportional to the forces.

The second law of motion might actually be easier to understand when expressed mathematically. Let

Now the second Law of Motion states that the rate of change of the momentum of an object is directly proportional to the

net force applied to it, and the change in momentum takes place in the direction of the applied net force, thus, let

once again

To see that the first and second law of motion are consistent, assume that an object has zero net force acting upon it, then the acceleration of the object must be zero, which means that the object is in a state of uniform motion. Conversely, if an object moves with uniform motion, its net acceleration is zero as well, and thus it has zero net force acting upon it.

As an example, assume that the net force acting on a car has a norm of

Impulse and Momentum Transfer

Now in classical mechanics, an impulse,

As another example, which will eventually lead us to momentum transfer, in a later tutorial though, note that a bee

with a mass of

In other words, using the impulse equation from above,

Variable-Mass System

The above theory is only valid for objects with a fixed mass. Any mass that is gained or lost will cause the momentum to

change, without an external force being applied, and thus different equations are necessary to model systems with a

variable mass, such as, for example, rockets. Rockets burn fuel and then eject spent gases, that is, for a rocket, its

mass is another function of time:

Observing that the above formula does not play well with Galilean invariance, is enough to note that it is simply wrong.

To derive a correct equation of motion for an object with variable mass, one must apply the second law of motion to the

entire system, which once again has constant mass:

One such formula is the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation,

derived from the above equation by the Russian engineer, and one of the fathers of modern

rocketry, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky:

Newton’s Third Law of Motion

The original citation of Newton’s Third Law of Motion is as follows:

Lex III: Actioni contrariam semper et æqualem esse reactionem: sive corporum duorum actiones in se mutuo semper esse æquales et in partes contrarias dirigi.

Translated to English, this reads:

Law III: To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

The third law of motion simply states that all forces between two objects exist in equal magnitude and opposite

direction, that is, if an object

An important example of Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which we encounter all the time, is that of basic movement. When we walk, we push against the floor, and the floor pushes against us. This is easier to imagine when swimming: a person interacts with the water, pushing it back, and the water reacts by pushing that person forward.

Normal Forces

Going back to one of the examples at the beginning of this tutorial, imagine an object lying on a table. In the figure, the weight pulled at the object and another force pushed it upwards. This is the principle of action and reaction. The reacting force is always perpendicular to the acting force, and called the normal force. In this case, the cause for the reaction force is that the top of the table fights against being compressed, no matter how small that compression might be.

This was a rather short and theoretical tutorial, but it was necessary to better understand the principles of classical mechanics. In the following tutorials, we will study some applications of Newton’s Laws of Motion, such as friction, strings, springs, translational equilibrium and circular motion.

References

- Geogebra

- Physics, by James S. Walker

- Tricks of the Windows Programming Gurus, by A. LaMothe

- Wikipedia